Thank you to everyone who responded to my last post asking for nature-writing recommendations. I’ve added a good many to the list, so definitely stop back in for new inspiration.

And an update: Things of Beauty #2 featured resources for a deep-dive into wolf recovery in the United States. Two new pieces add additional perspectives that wolf-lovers may find interesting:

The first, an opinion piece by Erica Berry (author of Wolfish: Wolf, Self, and the Stories We Tell About Fear) in the New York Times, shows wolf recovery may be less controversial than it’s commonly portrayed in mainstream media.

The second is a High Country News report by the always-fabulous Ben Goldfarb, investigating the ways Colorado hopes to smooth the path for its new wolves by pacifying their enemies in the cattle ranching community.

Now on to a few beautiful things!

1. Beautiful News

I wrote somewhere the other day, “Ecological restoration is my love language.” Yeah, that phrase is hokey, but it really is a good shorthand for the things that make one’s soul sing. Trying to fix what our species has broken, trying to return what we’ve stolen, and trying to heal what we’ve harmed — these are the stories I love.

For such a seemingly simple concept, it sure can get controversial. And lots of parameters need definition on a project-by-project basis: what, exactly, is the condition we are trying to restore? What other species may be harmed in the process, and can we justify that? What impacts will the work have on vulnerable humans, and are they equal stakeholders in decision making?

And this might be the hardest question of all these: how do we account for the changing climate?

It’s important to try to restore some of what we’ve broken without perpetuating the systems and harms that led to the destruction in the first place. Derrick Jensen wrote recently, in regard to the complex tradeoffs of ecological restoration: “One size fits one.” I took that to mean that caretakers must freshly evaluate the tools and goals for each restoration or rewilding effort, knowing that every project will require different means for different ends.

And so, I was delighted to come across this Guardian piece on an effort the U.K. National Trust is undertaking to plant 50 hectares of future Celtic rainforest across three parcels in north Devon. For non-Brits, that’s the southwestern corner of England.

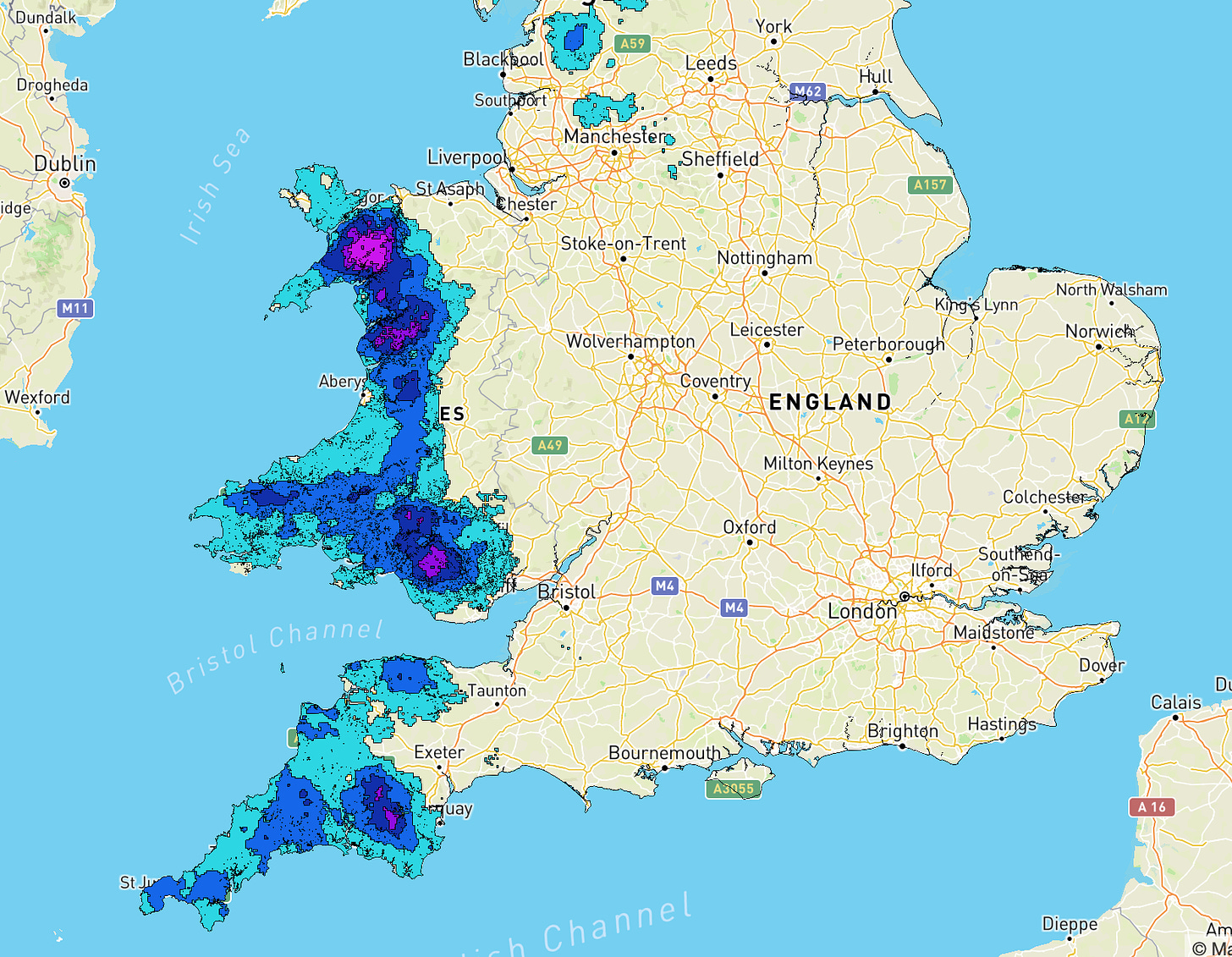

The temperate Celtic, or Atlantic rainforest, once covered much of the western edge of the island. Here is a map showing the ecosystem’s (possible) previous extent, covering around 20% of Britain. It is now down to about 1% of the island, limited to tiny patches scattered across its former extent. But oh, imagine the deep forest that once covered the colored areas below (the color gradations show varying rainfall patterns).

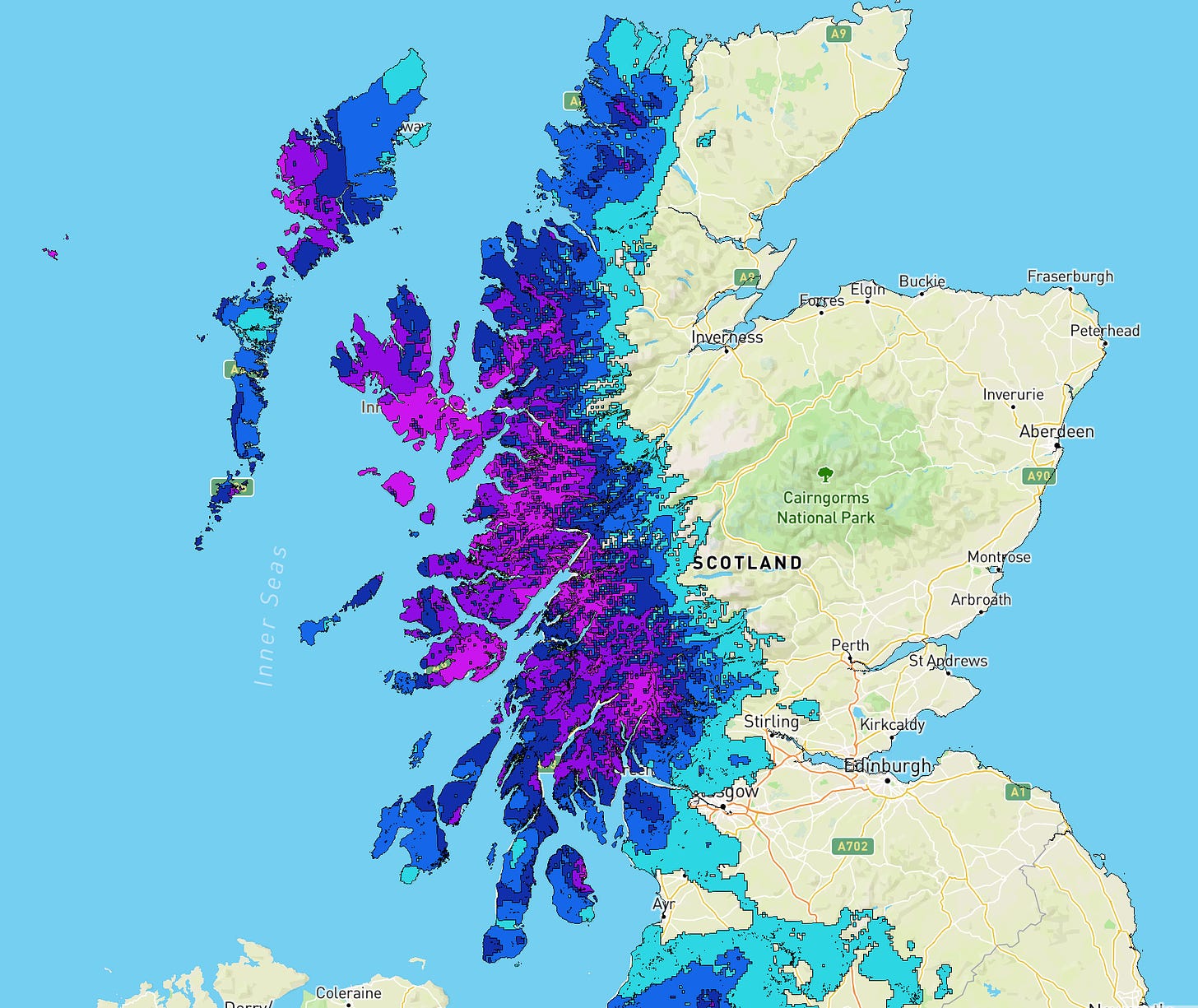

And here was its likely range across Scotland, some centuries ago. My goodness — can you just smell the damp, ancient branches, hear the quiet call of crepuscular birds, feel the forest mist on your skin as you walk the length of Scotland, never emerging from an unbroken canopy of green?

According to Lost Rainforests of Britain, a citizen-led effort that has worked to raise awareness and support for this globally important ecosystem, few people realize the British Isles were once home to such an extent of lush forest. The photo below highlights “the hallmarks of British temperate rainforest: polypody ferns, mosses and lichens carpet branches on trees growing along the O Brook, Dartmoor.”

How wondrous.

I hope to visit someday, but I will not live to see the lichens regenerate to their full glory, which is estimated to take at least a century. But here, I see a gift to unborn generations, one which I hope will be greatly expanded in future such that perhaps, someday, the U.K.’s inhabitants will have forgotten they once almost lost their rainforests entirely.

2. Beautiful Book

Speaking of Celtic imaginings, I’ve recently finished Sacred Earth, Sacred Soul by John Philip Newell, former warden of Iona Abbey in Scotland. This book won’t be for everyone. But I share it on the chance that someone might find in it a measure of peace.

I was raised in the Methodist Church in central Texas. There’s a lot of baggage there, to say the least, and Texas during my childhood was not a great place to be a fiery, adventurous girl.

As a young woman, I never understood the emphasis on doing good while on Earth so as to receive a reward, later, in heaven.

Even in the brown, flat, and dry landscape I grew up in, I knew that this was Heaven. Here. This gorgeous Earth. And that whatever God my elders expected me to worship, hadn’t he created the plants and animals we killed in the name of profit and progress? Why didn’t anyone bother to ask this God if he was okay with all the murder of nonhuman lives, the mesquite trees and the rattlesnakes, too, which he presumably loved as he loved us?

I left the church in my teens, finding no home in it for an Earth-loving soul who questioned the myth of human supremacy. Now, decades later, Newell’s writing has brought me around to a way of thinking about the immanence of God within Earth. He describes a Celtic understanding of Jesus-as-messenger sent from God-as-universe to remind humanity of a truth held within us all, one which most had forgotten: “the earth is sacred and this sacredness is at the heart of every human being and life-form.”

Welsh monk Pelagius wrote in the 5th century CE that “when Jesus commands us to love our neighbours, he does not mean only our human neighbours; he means all the animals and birds, insects and plants, amongst whom we live.”

This is the evolution of a Christianity that arose among Celtic people organically rather than being imposed by the Roman Empire, whose sway remained limited in pockets of the British Isles. These people accepted the message of Jesus as “their Druid (spiritual teacher), and the teachings and myths that had come down to them from their past were like an ‘Old Testament’ that preceded Christ, not a contradiction to Christ.”

Thus having arisen from a tradition in which male and female leadership were valued, nothing is found in Celtic Christianity to debase women, unlike many other forms of the religion that dominate today. (Perhaps especially in the United States.)

According to Newell,

“What most endangers us as an earth community today is that we have neglected our interrelationships—as countries, faiths, and races. The reality is that we need one another. We will be well to the extent that we all are well. We will be truly strong to the extent that we faithfully protect one another’s well-being, not simply the well-being of our people, our community, or our species. The strength of the sacred feminine is deep within us, in both men and women, young and old. It is awakening again in our depths. We need to open to it, now, if we are to be well.”

Amen to that.

3. Beautiful Art and Writing

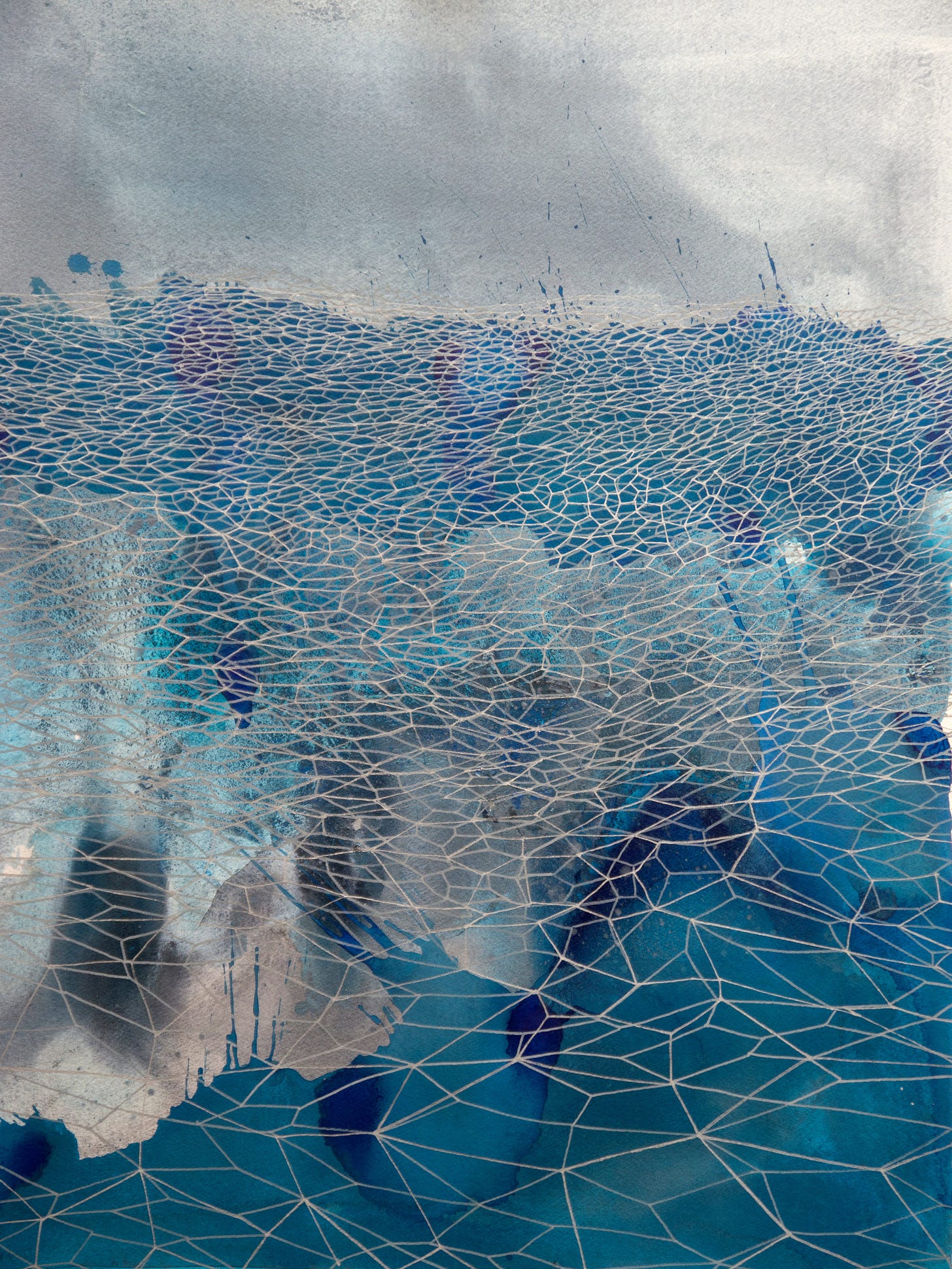

Samantha Clark publishes The Life Boat, a compendium of meditations on the environment of Orkney, plus the internal landscape, with her photography and paintings throughout. It’s gorgeous, and you can see the influence of the color and geometry of the place in her work. Here are a few to get you started, and you can find the rest for yourself at her site.

4. Beautiful Poetry

Big Tree Something

David Oates1

When I walk by the big trees

with their big shade, their big quiet,

something

olive in the nose, the eyes, the

leaf and sway, something makes me

regardful.

And now that I am old so many faces

seem beautiful too, even homely ones might have that

something,

and I’m so glad of a smile lately it’s embarrassing,

and couples of any kind—honestly, that tender

something.

What is that I’ve lived through, now skeining

out behind me, and still this woven now?

What must I be, what can it mean

that I keep trying to say?

If I play that sonata or prelude, what is it

that I am playing?

If I say my love, what are words

beside whatever our love actually is?

Yet if I keep silence, it is mostly pretentious

since I am always noisy inside.

These old trees hear right past all that. So

I am always standing in their big mind.

Something

will come to me, it always does, and I’ll wish

I could share it. But it’s not

that sort of

something.

5. Beautiful Admonition

Remember Maxine Hong Kingston’s words:

“Children, everybody, here’s what we do during war: In a time of destruction, create something. A poem. A parade. A community. A school. A vow. A moral principle. One peaceful moment.”2

To her list, I’d add: A garden. An ecosystem. A wild place. A warm home.

Create something.

💚

My best to all of you, and wishes for a week of wonder ahead.

-Rebecca

Published in Orion, Winter 2023.

Maxine Hong Kingston, The Fifth Book of Peace.

Highly recommend reading a new book called The Return of the Grey Partridge by Roger Morgan-Grenville — will make you feel hopeful about the future of the planet

Beautiful, Rebecca. Makes me feel like I've just been amongst the song leaves might make in soft rain, and mist.