I’ve highlighted below some writings that I hope will bring you a little peace and contemplative silence in this busy season. When I linked them, all (except the one I noted) were free to read, though this can always change.

Happy reading!

I found myself utterly swept away by Samantha Clark’s gorgeous piece, “Silence is Ecological.” In it, she relates how she met a nun, Martha, “someone with a deep, scholarly and practical understanding of solitude, silence and the contemplative life,” at a lengthy meditation retreat.

Martha, as the author later came to learn, was a Stanford-trained theology professor who’d written a pair of books on quietness, called Silence: A User’s Guide. On reading the books, the author notes they are “not for the faint of heart,” and really, isn’t that the truth for silence more generally?

Martha wrote: Communities are only as healthy as the solitudes that make them up, so that it is incumbent upon each of us to do the transfiguring work of silence.

Wow. That sounds like a mandate to me, and one I’m damn happy to shoulder.

More Martha:

The work of silence is so simple, yet to go against the grain of society and the culture is very difficult. But it is worth the effort: the work of silence…provide[s] stability and even joy in a disintegrating world. People who undertake to live like this become beacons, islands of safety where others can find a refuge. The resonances of silence permeate around them, whether they are aware of them of not.

Thinking of this view of silence as a requirement for a healthy society, my mind wandered to a study I read a while back, which laid the foundation for a proposition that noise makes forests ill. Turns out, trees need silence too.

In the first long-term study of the impacts of artificial noise on an ecosystem, the study’s authors looked at a New Mexico forest over a period of 15 years.1 The noise in question was generated by natural gas wells scattered throughout the study area. The researchers studied patches that were quiet at the beginning of the 15 years but became noisy when gas wells were later added, and they looked at patches that started out loud and became quiet when wells were shut down. They also cataloged sites that remained quiet through the entire time period.

What they found was unsettling. The sites with well noise had around 75% fewer seedlings compared to the quiet sites, meaning there’d be far fewer trees to grow into the next generation. And, other types of plants besides trees were less diverse in the loud areas.

Two mechanisms were proposed. One, that pollinators who help plants to make seeds would stay away from loud noises, so the trees and other plants near wells never got a chance to make many seeds in the first place. And two, the chronic noise would keep away birds, rodents, and other animals that help disperse whatever seeds do get made.

This effect persisted for years even after the noise source was removed. And it makes sense: one of the trees studied, a juniper, relies on mountain bluebirds, Townsend’s warblers, and grey foxes to carry away and “plant” its seeds. All of these animals are known to avoid noise.

As for pollination, there is some evidence that pollinating insects like bees, beetles, and flies may avoid loud areas because they communicate acoustically and need low ambient noise to hear each other. So the trees and other plants made fewer seeds, and had fewer animals around to disperse them, just because it was so noisy.

Elissa Altman writes movingly of a childhood spent in a noisy home, buffeted by the sounds of the Long Island Railway shaking her building day and night. She finds that “noise translates to the expectation and acceptance of chaos as homeostasis”; that not only does noise make you immune to noise, it makes you into a person who seeks noise to feel normal, to draft chaos in the wake of your relationships, personal and professional.

Grow up in a noisy world and you will lead a noisy life. I don’t know if this is entirely true. But what I do know to be true is this: grow up in a noisy world, and you will eventually stop hearing the noise. It will be reduced to a low, dull hum. A buzz. Your body will acclimate to the aural, constitutional assault, and out of self-defense, will grow accustomed to it. Fast forward: you will run the risk of being forever attracted to noise — the chaos and the drama — because it will be your normal.

Meg Conley at the Pocket Observatory speaks beautifully of the way women sometimes lack the silence needed to hear their interior voices, the way female writers can be surrounded by so many other voices that they wonder whether their own have left, never to return.

Some men get to listen to the voices in their heads, but most women have to listen for the voices in the hall.

The din of domesticity disrupted the other frequencies in my head. A liturgy forged in factories and blessed with holy oil. It thrummed across centuries, carried to me through policy and pulpits. The doctrine said the world contained many homes but the home could not contain many worlds.

When I read Cal Newport’s book Deep Work several years ago, I underlined, highlighted, and copied into my journal the following definition of solitude deprivation:

A state in which you spend close to zero time alone with your own thoughts and free from the impact from other minds.

Ahh, so. I was in the thick of young motherhood then; my offspring had a million questions and needs and random thoughts. I loved each little moment together, but I was also trying to learn a new legal field and build an environmental law practice. My life was so noisy.

Newport went on to note:

Solitude is not a pleasant diversion, but instead a form of liberation from the cognitive oppression that results in its absence. . . . [W]omen were denied this liberation by a patriarchal society. In our time, this oppression is increasingly self-inflicted by our preference for the distraction of the digital screen.

I picture a blue jay mother trying to teach her young ones how to collect pinyon pine seeds in the cloud of noise from a gas well in New Mexico. I bet she can’t even hear herself think.

Meg Conley’s lovely piece is here:

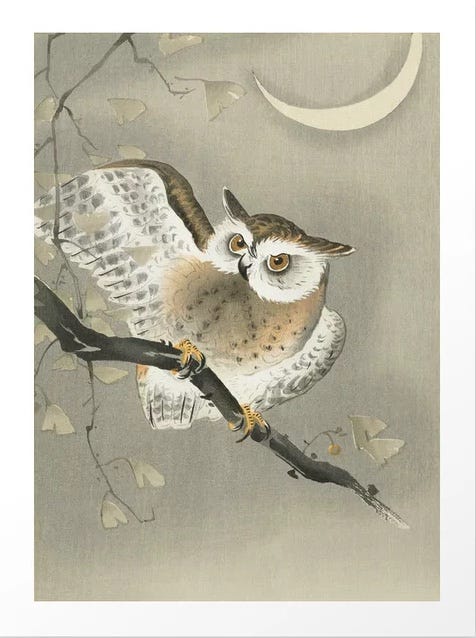

James Roberts at Into the Deep Woods is trying to record his favorite sounds as his range of hearing gradually narrows. None of the sounds he lists are manmade; he treks out with his recording equipment to capture “the voices of fast flowing rivers, owl calls and the wing-beats of goosanders.” His recordings keep getting interrupted, though, by the industrial world: “first a tractor, then a chainsaw, and finally the droning tinnitus of an overhead jet.”

He writes that, even as a young boy, he naturally tuned out what didn’t interest him, and that included those teachings that civilize.

When I was at primary school the teachers always moved me to the front row of the class because of my deafness, but I could hear as well as anyone back then. I just wasn’t interested in what they were teaching me. It felt like there was something outside the classroom walls that I was missing, something important but invisible, happening beyond the housing estate, the railway line and the pit stacks. There was a line of trees on the horizon and I knew that whatever I was sensing was going on somewhere in there.

James grew up in range of constant engine noise but later chose a path of quietness, of listening to a single owl. Now, the noise of the artificial world is slowly tuning itself out for him, and what will remain are the sounds he loves. It’s a beautiful meditation on what makes our ears sing.

Finally, the fabulous Ben Goldfarb writes in High Country News about Walt Whitman’s blab of the pave, the maddening road noise that he experienced like a wound when visiting New York City. Humans, like forests, live lives truncated by noise; Goldfarb tells of a French study claiming that noise may rob three years of life from Parisians living in the loudest neighborhoods.

I wonder if James Roberts would agree with Goldfarb’s definition of sound versus noise. Contrary to our normal usage, Goldfarb considers them antonyms:

Sound is fundamentally natural, and tickles the ears is even the quietest places: the susurrus of wind, the drone of a bee, the starched snap of a jay’s wings. Noise, by contrast, is a human-produced pollutant, and like its etymological root, nausea, it’s unpleasant.

In describing the 3-mile wide sonic shadow of a road through Glacier National Park, he notes it’s a form of habitat loss. In our “windshield wildernesses,” birds and other small animals must look for predators rather than listen for them, because who could hear the wingbeats of a stooping hawk over the roar of a 45-foot RV barreling down the highway in the valley below? Every moment spent looking for a predator is one less moment a small animal spends foraging and eating. Birds in the sonic shadow of Glacier’s Going-to-the-Sun Road were, under experimental conditions, thinner and weaker than those in quiet areas.

The essential insight of road ecology is this: Roads warp the earth in every way and at every scale, from the polluted soils that line their shoulders to the skies they besmog.

Among all the road’s ecological disasters, though, the most vexing may be noise pollution—the hiss of tires, the grumble of engines, the gasp of air brakes, the blare of horns. Noise bleeds into its surroundings, a toxic plume that drifts from its source like sewage.

So, where does this leave us, in a world polluted by noise? It’s yet another conundrum without an easy answer, but I hope that each of you finds a bit of the silence you need this winter.

Phillips JN, Termondt SE, Francis CD. 2021 Long-term noise pollution affects seedling recruitment and community composition, with negative effects persisting after removal. Proc. R. Soc. B 288.

If your email inbox ever feels overstuffed with Substack emails, you can turn off email notifications, which will allow you to receive new post notifications only when you visit the Substack app or website. This will prevent newsletters from filling up your email inbox, if like me, you’re subscribed to a LOT of writers. (If you don’t know how to do this, let me know, and I can list the steps for you.)

For me, this has been a crucial action toward reducing my own overwhelm: there are so many beautiful things I want to read here, but I need to be able to do so on my own schedule. Maybe this tip can help you find some serenity if email clutter disheartens you.

I’m reminded of this long digression by Italy Calvino at the beginning of a short story called The Adventure of the Poet. I won’t burden the comment section with the full page, but it begins

“In fact every silence consists of the network of minuscule sounds that enfolds it: the silence of the island was distinct from that of the calm sea surrounding it because it was pervaded by a vegetable rustling, the call of birds, or a sudden whir of wings.”

Love this piece! I find myself very sensitive to sound in general. I live in Miami, Florida. I'd argue it's as noisy as any City. Interesting to see the route of noise, nausea. When there's too much noise I do get physically nauseous! Don't get me started on the leaf blowers! They are ubiquitous. Which is funny because they are fairly pointless. What's interesting is a lot of folks feel the way I do but we do nothing about it. Sidebar, Antonia Malchick who's substack , on the commons, also writes about "the Walking Life", about her efforts to reshape the community away from roadways and favoring more pedestrian infrastructure. It all ties in! You can tell my mind is all over the place on this. Anyway ,I appreciate your writing. Thanks!