“Owl in America” is a series of letters chronicling the next four years from the perspective of an environmental lawyer. Practicing conservation and public-lands law during the first Trump administration was an exercise in hope and dogged persistence amidst the ever more effective demolition issuing forth from Washington, D.C. Much ground was lost, only some of which was regained during Biden’s four-year term. This time around, I’m taking notes.

Hi all~

I am particularly fond of coastal snowy plovers. These tiny shore birds move like windblown seafoam across damp sand on the Pacific and Gulf shorelines of the U.S. They run as a group somewhat as the more familiar sanderlings do, but with less of a “chasing the waves” pattern. Their chicks join the beachy foraging fun within three hours of hatching, and as you can see, serve to make the flock even more adorable, if that is possible.

Dogs also find them irresistible, which is how I came to learn about them during my college years in coastal California, in the early 2000s. My very best friend was a jindo, a rather uncommon breed of Korean dog that I’d rescued from the side of Highway 101 in Los Angeles when she was a tiny puppy. They are semi-feral small game hunters in their native Jin Island, and my buddy was cut from the same cloth. I discovered this when I’d take her to a beach and she’d disappear half a mile down the shoreline in pursuit of some poor seabird (she never caught one, but I’m sorry to say she harassed many).

One day, I noticed an area of the foredunes had been roped off, and while my dog was off on the chase, I wandered over to take a look at the placard. It was a Fish and Wildlife Service notice informing beachgoers the closed area was breeding habitat for the federally threatened Pacific snowy plover. Humans and dogs were prohibited from entering for the remainder of the breeding season.

I’d never heard of a plover, but duly restrained my dog from crossing the mostly symbolic barrier. Other people didn’t. Still, the rope was enough to deter some human traffic.

The next week, I visited the ornithology department at my university and learned that plovers nest right in the sand, making their eggs vulnerable to trampling and predation. Their only defense is camouflage: the tiny, speckled eggs are almost impossible to see, even when you’re standing directly over them.

Species declines generally have a myriad of causes, but habitat loss (i.e., development and agriculture) is typically the foremost. For plovers, it’s habitat loss, too, but much of the Pacific coast is undeveloped and permanently preserved as public land. The snowy plover’s recovery is one of the few for which, these days, the main impediment is human behavior: trampling underfoot, crushing with vehicles, horseback riding, and off-leash beach dogs.

This year, I was back in Northern California during snowy plover breeding season and decided to visit Little River State Beach to see what was new with my wee bird friends. Right away, I noticed clear signage at the parking lot and trailhead indicating that dogs were allowed only if leashed, and only on the wave slope (not on the dunes).

The undulating path through the scrubby dunes to the beach was hard to follow, and despite being highly aware of the closure, I found at one point I’d crossed the rope inadvertently and ended up walking in the closed area. I carefully backtracked, watching where I placed my feet until I found the trail again. Other people may not have realized or cared they’d gone astray and would have presumably stumbled on through the dunes with their kids and dogs until they reached the water.

When I arrived at the beach, rope barriers marked off the foredunes habitat area from the packed sand of the wave slope. I saw a trio of large dogs gamboling joyfully (without leashes) from the water’s edge up into the dunes and back, wrestling and tumbling all the way. I saw a pair of horseback riders moving at a slow trot along the dune crest. Looking both ways along the waterline, dogs were running freely as far north and south as I could see. A group of people had set up a picnic blanket in front of the closure rope and their pack of kids had made a game of jumping over it and racing to hiding spots in the folds of the dunes.

The rule-enforcer part of me wished a federal wildlife officer would appear and give all these oblivious humans the what-for. But the once-oblivious dog lover in me, and the mother who rejoices in seeing kids play freely in nature, understands why they’re all there.

The most recent federal status report on the snowy plover estimated just over 2,200 adult plovers survive along the 1,300-mile-long Pacific coast of the mainland U.S. The beach I visited this year is one of the few remaining breeding sites for this rare little being. So, how is it possible we are not doing everything we can to give them the best chance possible? Especially when the solution is relatively simple to imagine, compared to the thorny problems usually involved in environmental work?

Right? The answer must be to completely close the beach for the plover breeding season. It’s state-managed land from highway to ocean, there’s no infrastructure that workers need access to, and there’s no private property that landowners need to reach. As far as I can discover, though, no closure has been tried.

As a civil lawyer married to a mental health care provider, I’m a big fan of pragmatically accepting human nature as it is, including the things we can’t help but prioritize—our families, our fun times, our dogs—and crafting solutions that account for them. In the plover dune closure example, 20 years of obvious failure of the “good-faith rope” system is long enough to prove to me it doesn’t work. In 2005, there were an estimated 41 snowy plover adults along the entire north coast of California. As of the most recent status report, that number remains at 41. I don’t call that recovery.

Depending on people to do the right thing in order to solve ecological problems doesn’t always take into account human nature. People are going to trample through the dunes, whether they don’t care or whether they mean well but get lost, like I did; they’re going to let their dogs run off-leash even on public property that forbids it; they’ll let their kids play hide and seek in fragile habitat.

That’s okay. We’re not going to change. So couldn’t we close this beach for a few months each year? Knowing the way we are—the way we can’t help but be—couldn’t we just keep ourselves away for a while? Could we put a small limit on ourselves to give these little birds a chance to recover? They have just as much right to exist here on Earth as we do.

That brings me to Trump. (Doesn’t everything, these days?) The kind of hypothetical beach closure I’m talking about would have to come from the federal Fish and Wildlife Service, with the cooperation of the state parks department and probably the local government. A public process would be involved, with publication of review documents and hearings. Signs would have to be made. Enforcement officers would have to be hired to patrol the beach. Public education campaigns would have to occur. Lawsuits would have to be defended. Field researchers would have to be hired to monitor the plover population for several years to determine whether the closure benefitted it. All of that costs a lot of money.

This beach closure idea is meant to illustrate where federal endangered species funding goes (and how many steps it takes to implement even something as “simple” as an area closure). When we speak of “recovery funding,” some version of the above is what we’re referencing. Behind the scenes, these efforts also include university partnerships for genetic analysis, funding for captive breeding programs, money for state-level recovery programs, and so much more. (That’s not to mention all the years or decades of biological survey work that goes into even asking the federal government to list a species in the first place, often carried out by university wildlife departments and volunteer groups.)

Even under “environmentally friendly” administrations, there is never enough money allocated for all this work. So year after year, wildlife officials string up their frayed ropes and peeling laminated signs hoping, I suppose, that maybe this year the beachgoers and tourists will leash their dogs.

Endangered species recovery work requires a well-funded wildlife agency, and by extension, a funded and functional Department of the Interior, which oversees it. The richest nation ever to have existed on Earth should be able to scrape up the money for this, but a group of the richest humans ever to ever existed on Earth will soon descend upon the government like a plague of locusts and have indicated their intent to further strip away science funding.

The incoming locust-in-chief has nominated billionaire Doug Burgum to head Interior.1 Almost 5,000 people left or were fired from the Interior Department during Trump’s first term. A similar or greater attrition is predictable, starting in January; although Burgum is expected to work toward streamlining drilling and mining on public lands and will need staff to do that, he’ll almost certainly search for savings among agency science programs.

Cuts to federal science funding would extend far beyond endangered species recovery, of course: there’s federal climate research, earthquake and tsunami warning systems, mapping, green chemistry, botanical surveys, and a kaleidoscope of other initiatives in just the environmental and earth sciences alone. Musk and Company will be recommending huge budget cuts and these programs are certain to be affected.

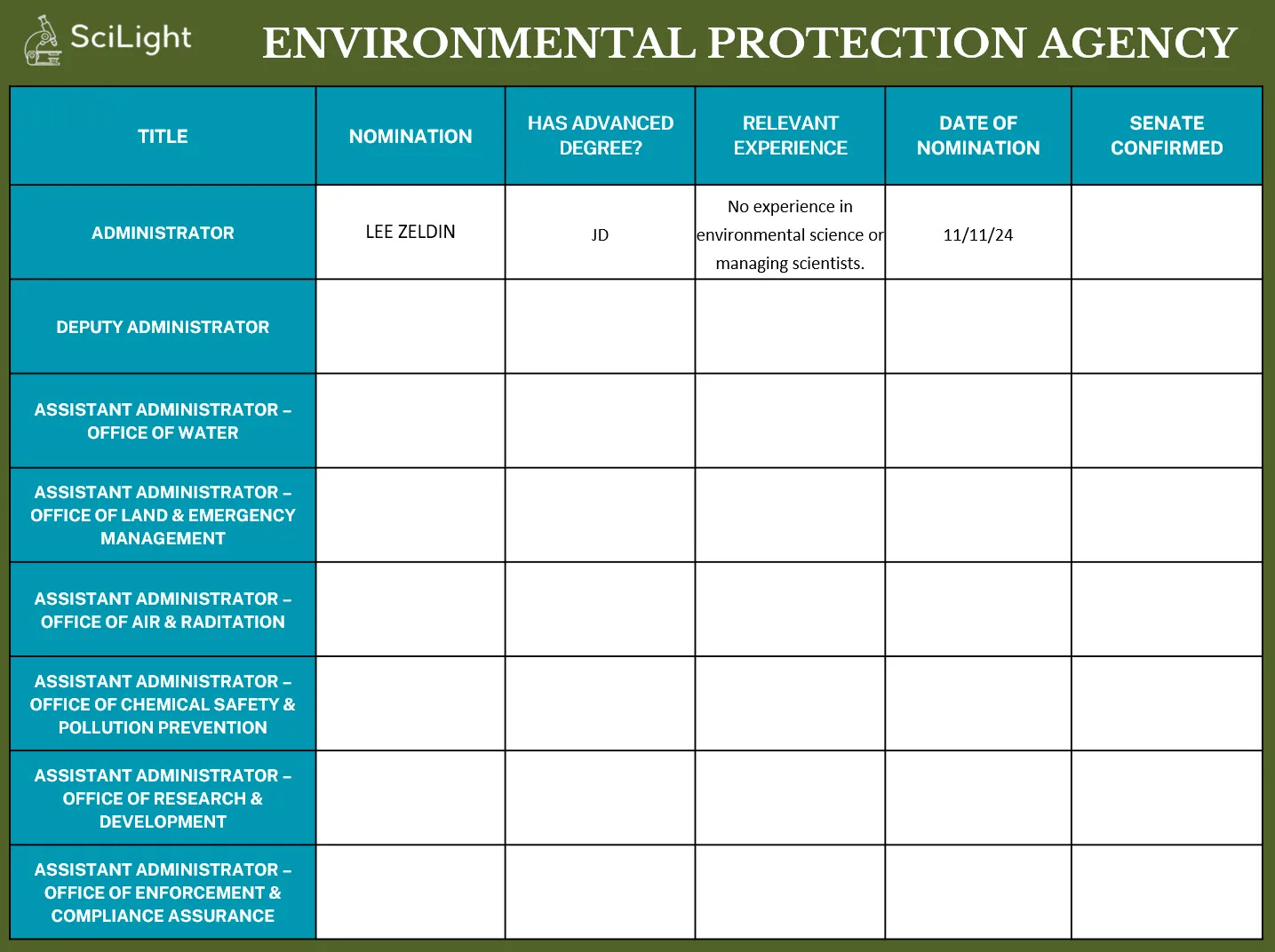

The researchers at SciLight have put together a couple of useful tools for those who want to follow this closely. One is an appointment tracker listing nominees for crucial scientific and regulatory positions.

The other is a toolkit for agency scientists, informed by lessons learned during Trump I, that details “Information on rights, protections, and resources available to defend science for the public good.”

But back to the little plover. Today’s post was sparked by a photo caption in nature writer Ken Lamberton’s piece about birdwatching while on vacation in Southern California. His favorite sighting was a banded snowy plover, which he photographed and reported to the U.S. Geological Survey’s bird banding program. The program, which has been around since 1923 and tracks birds together with Canada as part of a North American bird banding coalition, receives over 100,000 reports of banded birds every year.

Lamberton wrote:

I reported this plover to the USGS website for banded birds and received a response today. According to the coordinator, the plover was found sick at nearby Camp Pendleton late summer 2023 and taken to SeaWorld for rehab and banded before released back at Pendleton. It has only been sighted a few times, with no sightings during the breeding season. The coordinator said it was good to see the plover was still thriving.

How gorgeous is that? There’s an anonymous government employee somewhere in the U.S., working in front of a computer screen in some branch of a science agency, who knows this single snowy plover “by name” and cares about that little bird’s wellbeing. That agency staffer is actually someone who Makes America Great, and I’d take them over a hundred Elon Musks, any day. Whoever that person is, I fervently hope their job survives what’s coming.

Talk to you soon,

Rebecca

Sources:

https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/five_year_review/doc6166.pdf

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2024/dec/01/doug-burgum-trump-interior-secretary-drilling

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-04098-3

https://www.usgs.gov/labs/birdb-lab/about/bird-banding-laboratory-what-we-do

https://kenlamberton.substack.com/p/the-big-yard-notes-from-a-pajama-d57

*Inspired by historian Heather Cox Richardson’s Letters from an American.

You can reach me at fearlessgreen@substack.com

No shade on actual locusts. They have their own place in a healthy ecosystem.

I have been called a misanthropist and in some respects am. I admit to valuing that little bird over the entire incoming administration. But as you say, people are people and children will play, dogs go off-leash and signs ignored. There are simply too many of us, good actors and bad actors alike. Even if there were ten St Francises walking in the beach they would still inadvertantly crush the little speckled eggs. Habitat destruction, the extinction of species, the obliviousness of power and privilege. Too many of us.

Can people come together to start teaching school aged kids about the area? Actually going into classrooms and talking about them. Start with our young.