“Owl in America” is a series of letters chronicling the Trump years from the perspective of an environmental lawyer. The first administration brought chaos to the framework of laws that protect America’s public lands and wildlife, only some of which was repaired during Biden’s term. It remains to be seen whether the increased preparedness of incoming policy-makers will result in increased efficacy at dismantling the executive agencies that administer these lands and protections. These notes will document that transformation.

Hi all~

Happy New Year, even if you, like me, are feeling a bit like this:

Might as well lead with the great news. Today, Biden has designated two new national monuments in the western U.S.: the 624,000-acre Chuckwalla National Monument in Southern California and the 224,000-acre Sáttítla Highlands National Monument in the northern part of the state.

The Chuckwalla National Monument, named after the stocky lizard emblematic of that region, lies:

at the confluence of the Mojave and Colorado Deserts, showcasing an awe-inspiring landscape of mountain ranges, meandering canyons and washes, dramatic rock formations, palm oases, and desert-wash woodlands. Its natural wonders include the Painted Canyon of Mecca Hills, where visitors can wind through towering rock walls and marvel at the landscape’s dramatic geologic history, and Alligator Rock, a ridge that has served as a milestone for travelers for millennia. The region is also home to more than 50 rare species of plants and animals, including the desert bighorn sheep, Agassiz’s desert tortoise, and the iconic Chuckwalla lizard, from which the monument gets its name. (White House Press Release.)

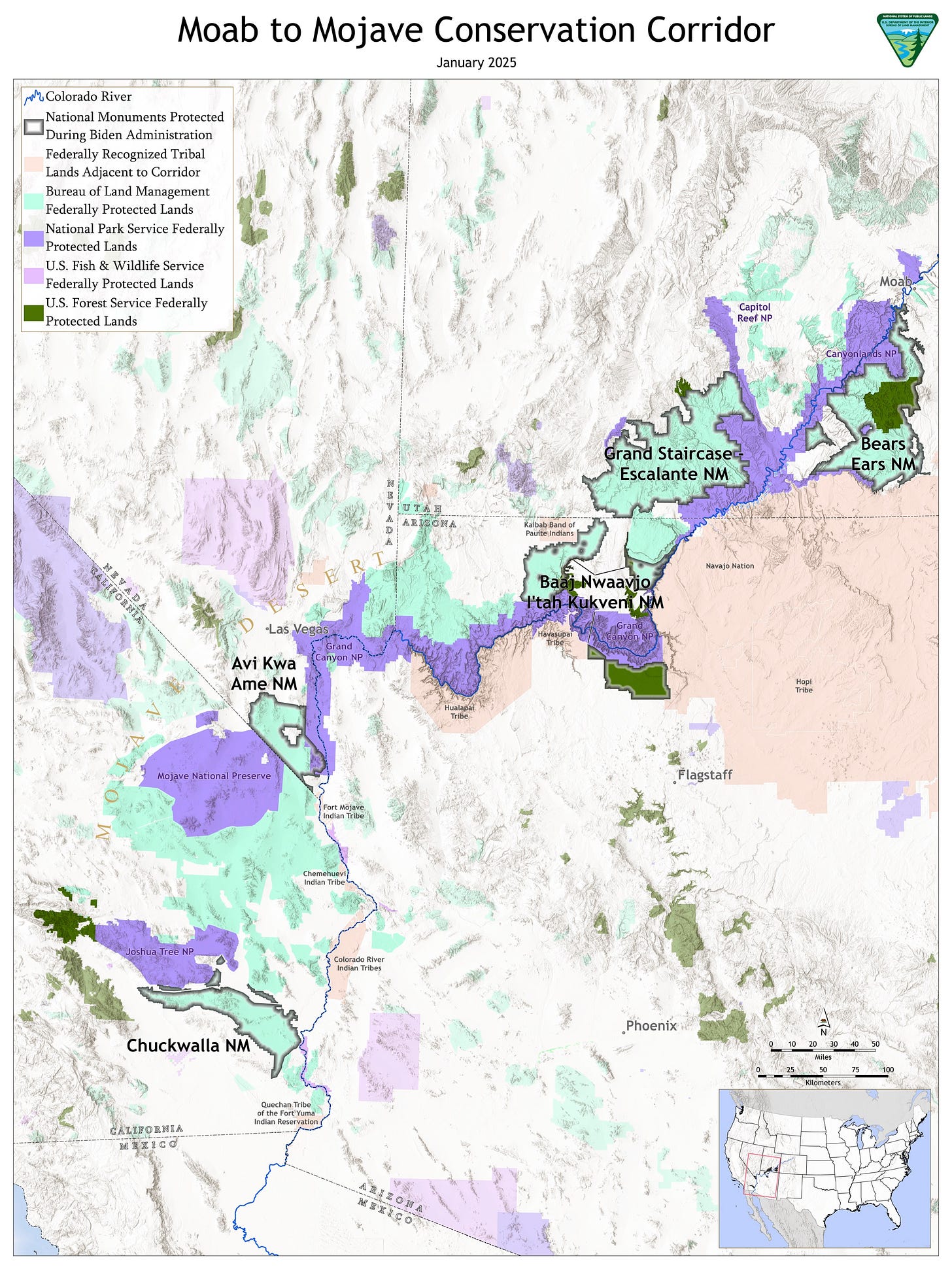

The Chuckwalla monument fits as one of the final pieces in the U.S.’s largest patchwork of protected lands: stretching 600 miles from Utah to California, it is now known as the Moab to Mojave Conservation Corridor.

This proposal was a key part of Biden’s America the Beautiful initiative to set aside 30% of America’s land and waters for conservation by 2030. According to the White House:

The Moab to Mojave Conservation Corridor stretches from Bears Ears National Monument and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in southwestern Utah, to which President Biden restored protections in 2021; through Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni – Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument in Arizona and Avi Kwa Ame National Monument in Nevada, both established by President Biden in 2023; and reaches the deserts and mountains of southern California that are being protected with today’s designation of the Chuckwalla National Monument.

Today’s other designation, the Sáttítla Highlands National Monument in northern California, represents the culmination of decades of advocacy by the Pit River Tribe to protect their sacred sites around the dormant Medicine Lake volcano. Using the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and other federal laws, the tribe has litigated effectively—and repeatedly—to prevent logging and geothermal drilling in the areas, now managed by the U.S. Forest Service, that were their homelands for thousands of years. They led the coalition pressing the federal government to protect these lands permanently.

With the addition of these two new monuments, the Biden administration has conserved the largest total land and water area of any presidency. Drilling, mining, solar-energy development and other industrial uses will be restricted while other activities like recreation and grazing will be permitted, subject to tribal consultation.

Tribal nations spearheaded these efforts; back in December 2024, I wrote about a few other national monuments Biden has newly established and mentioned a few that were still on activists’ wish lists prior to the new administration. Today, he signed the documents making two more of those a reality, bringing his monument designations to 10 in total.

The outgoing team is working with alacrity to protect America’s lands. As for the incoming administration—based on first-term actions that included shrinking previous monument boundaries plus explicit plans within Project 2025 to undermine the law that allows for presidential monuments—we can almost certainly expect challenges to the new protected areas. But until that happens, let’s take the win.

I love America’s public lands. They are my deepest passion. As a young woman, I had what I’ve long thought was the world’s greatest job (until it was displaced by one I’m going to tell you about later in this letter): I worked for the U.S. Forest Service, and my entire job consisted of documenting backcountry water sources high in the alpine forests of eastern Arizona. Armed only with a paper map, a compass, and this newfangled device called a GPS that could only mark where you’d been but couldn’t actually direct you anywhere, I’d find and photograph various springs, or seeps, or rancher’s wells. Then I’d click a button on my huge GPS box to mark the coordinates, and map a course for the next point of interest, often miles away through some of the most beautiful mountains I’ve ever seen. This data was later mapped into a forest-wide hydrology database that provided information to scientists and planners and helped the Forest Service parse the impacts of logging, wildfires, grazing, and climate change on the area’s ecosystems.

My time in Arizona’s high-elevation forests made me into a new person. It was the first time I’d ever walked among old-growth trees. Just on the border of the national forest and the Apache Nation, these mixed pine and fir stands had never been logged. Fire scars showed they’d certainly burned at intervals—there was lots of lightning in those mountains—and some of that was likely from intentional fires set by Apache firekeepers prior to colonization. The result of that non-industrial (dare I say ‘natural’) management over centuries to millennia, was a colonnade of massive, golden-brown ponderosa trunks, widely spaced with berry bushes and sweetly scented, springy duff making up the forest floor in between.

I grew up in a heavily modified landscape, the ranch lands and metroplex-suburban areas of northern Texas. I’d never experienced an intact ecosystem before. I had never felt what someone with even a modicum of sensitivity feels washing over them in such a place: the intelligence of self-willed nature. It’s undeniable once you’ve sensed it, and it’s why old-fashioned environmentalists still fight so hard so keep some places off-limits from human meddling. There are so few of them left.

One day, I was miles from the nearest road (and that was just a dirt track) and hadn’t seen another person since I left the ranger station that morning. A herd of dozens of Rocky Mountain Elk—the males almost twice my height with their summer antlers on—thundered past me bugling, close enough to smell their musky fur as I trembled behind the trunk of a ponderosa pine. The atmosphere in their wake was charged—scented, yes, but also vibrantly alive in a way I’d never felt.

After they’d moved on, I could no longer resist the call: I lay down for the rest of the afternoon on that spongy forest floor and watched the sunlight sparkling across my body in lime-green motes. Years later, when I first heard the Japanese terms komorebi—sunlight leaking through trees, and shinrin-yoku—forest bathing, I understood them in my soul.

After Arizona, I finished my biology degree and was hired by the Forest Service in Northern California to run the wildlife department (of which I was the only employee) for an extremely remote ranger district deep in the heavily forested coastal mountains. Although I’ve shared a few stories, I haven’t publicly told all the tales from my time there. Suffice to say that the heartbreaking decisions I witnessed while working for a timber-dependent agency—decisions which led to the deaths of threatened and endangered species—drove me to change to a career path that had never remotely occurred to this wildlife-crazy nature girl: the law.

Like documentary filmmaker Ken Burns, I think our national park system (along with our other public lands) was America’s Best Idea. Although it suffered in execution in important ways that violated indigenous rights—by which I mean, the government forcibly evicted indigenous people from their homes to create some of the parks—I believe the system could be reformed under the sensitive and intelligent leadership of concerned tribal and federal officials to remedy some of that original sin. Whether sensitive and intelligent federal leadership will be available in the near-term, this is at least a longer term aim we can keep in mind.

National parks are only a small portion of our public lands, though: other agencies like the Fish and Wildlife Service and the Forest Service, for which I worked, manage a far greater area. The nation’s largest public land holder, though, with over 10% of U.S. total land area, is the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Jokingly called the ‘Bureau of Livestock and Mining’1 by conservationists weary of its perennial prioritizing of extractive activities over conservation, the agency recently received a nice overhaul courtesy of the Biden administration’s Public Lands Rule.

Flying below the radar of most press coverage, this signature achievement crystallized decades of pressure to force the government to value conservation as highly as logging, ranching, drilling, and mining on an enormous swath of public lands. BLM operates under a “multiple-use, sustained-yield” mandate per federal law, which has in practice resulted in 90% of that land being available for one ‘use’: oil and gas extraction.

The new Public Lands Rule explicitly defines conservation as a ‘use’ such that the agency must balance it equally with extraction: “Conservation is a use of public lands on equal footing with other uses and is necessary for the protection and restoration of important resources.”

The new rule recognizes that “BLM’s ability to manage for multiple use and sustained yield of public lands depends on the resilience of ecosystems across those lands.” While such a statement may seem self-evident to anyone with an ecological education, it marks a step forward for an agency whose guiding mission has seemed to prioritize extractive use.

Conservationists and tribes have long wished for the ability to lease land for conservation purposes, and activists from time to time have attended lease auctions and won leasing rights for ranching or oil drilling, with the intention to hold those lands without carrying out the intended ‘use’. The goal was to prevent certain parcels from being degraded, sure, but also to bring awareness to how federal land management has historically been stacked against preservation. Activists have been jailed for bidding on extractive leases with no intention to ever drill there; now, the new Public Lands Rule makes it legal for third parties, such as tribes and nonprofit groups, to bid on public land leases within the BLM system to put them to ‘use’ for ecological restoration. It’s a change that holds the potential to radically alter the downward trajectory of ecosystem health on many of our public lands.

The Public Lands Rule was finalized last spring. The BLM’s guidance documents indicate they intend to continue implementing it (as they must). When and if a legal challenge or secretarial/presidential order arrives contravening its provisions, I will write about it here. In the meantime, as with all the new national monuments Biden has designated, let’s take the win.

One day about a decade ago, my husband and I were walking with our infant daughter on a trail along the coast of central California. We came around a bend to see a rangy, older man in a beige uniform fiddling with camera equipment aimed toward the ocean. My gregarious husband struck up a conversation about wide-angle lenses for outdoor photography, and before long, we’d gotten to know the BLM’s official landscape and wildlife photographer, Bob Wick. (This is the job I mentioned above that I think is even better than my old Arizona backcountry gig.)

That day, Wick was taking photos of big rocks or tiny islands rising from the waves just offshore: these are part of the California Coastal National Monument, established in 2000 by the Clinton administration to protect about 1,000 of these rocky structures, which provide habitat for a wide range of marine species along the Pacific Coast.

Working for the BLM for over 30 years, Bob Wick’s job consisted of traveling to some of the most beautiful places in the world, those managed by the BLM, and photographing them for the agency. He retired a few years ago, but a vast treasure trove of truly stunning photography is one result of his long career. Because he took them on behalf of our government, all these photos are in the public domain and free to use with attribution.

Now that you know his name, you’ll see photo credits for Bob Wick everywhere; just today, I’ve come across his work in the Los Angeles Times and The Washington Post.2 I’ll share a few of his images below just to give a sense of the wide types of landscapes BLM manages. Many of these places were protected only after lengthy campaigns carried out by dedicated people who loved a piece of land and fought—some for a lifetime—to see it protected under federal law.

Talk to you soon,

Rebecca

All photos below of various BLM-managed lands: Bob Wick, Bureau of Land Management

Carrizo Plain National Monument, California, 2017 superbloom

Giant sequoias in Case Mountain Extensive Recreation Management Area, California

Kasha-Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument in New Mexico

Ironwood Forest National Monument in southern Arizona

Sutton Mountain Wilderness Study Area in central Oregon

Harbor seals in the California Coastal National Monument

Sukakpak Mountain, northern Alaska

Cadiz Dunes Wilderness, California

Sources:

https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2025/01/07/fact-sheet-president-biden-establishes-chuckwalla-and-sattitla-highlands-national-monuments-in-california/

https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2025-01-03/biden-to-create-2-california-monuments-sacred-tribal-land

https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-solutions/2025/01/02/chuckwalla-stttla-national-monument-california/

https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/secretary-haaland-celebrates-president-bidens-designation-chuckwalla-national

https://www.reuters.com/world/us/biden-names-two-national-monuments-california-cementing-conservation-legacy-2025-01-07/

https://www.protectsattitla.org/protection

https://www.usda.gov/about-usda/news/press-releases/2025/01/07/usda-celebrates-president-bidens-sattitla-highlands-monument-designation

https://www.blm.gov/programs/national-conservation-lands/california/california-coastal-national-monument/history

https://www.blm.gov/about/laws-and-regulations/conservation-and-landscape-health-rule

https://www.blm.gov/sites/default/files/docs/2024-04/PLR_general-factsheet_508.pdf

https://www.colorado.edu/center/gwc/sites/default/files/attached-files/a_legal_analysis_of_blms_public_lands_rule.pdf

https://www.wilderness.org/articles/article/open-business-and-not-much-else-analysis-shows-oil-and-gas-leasing-out-whack-blm-lands

https://www.blm.gov/blog/2021-08-12/longtime-blm-photographer-bob-wick-retires-amazing-work-lives

https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2021/08/american-landscapes-seen-through-lens-bob-wick/619720/

*Inspired by historian Heather Cox Richardson’s Letters from an American.

You can reach me at fearlessgreen@substack.com

Wilderness writer Edward Abbey coined the phrase ‘Bureau of Livestock and Mining’ for the Bureau of Land Management/BLM.

Both papers that do solid environmental reporting but are saddled with compromised editorial ethics, I’m well aware.

This feels hopeful Rebecca, far to go but still this "the new Public Lands Rule makes it legal for third parties, such as tribes and nonprofit groups, to bid on public land leases within the BLM system to put them to ‘use’ for ecological restoration" must be much to smile about.

And, those really are two dream jobs, I'd take either one!

I was fortunate to be in Southern California during that 2017 super bloom. It was as astonishing as the photo suggests.